Wikipedia:

1700–1769

Throughout the 18th century, knowledge of Australia’s coastline increased gradually. Explorers such as the Englishman William Dampier contributed to this understanding, especially through his two-volume publication A Voyage to New Holland (1703, 1709)

1770: Cook’s Expedition

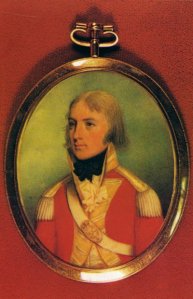

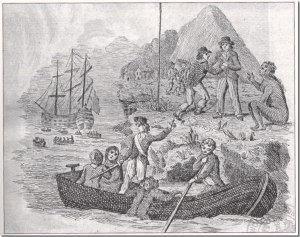

In 1768 British Lieutenant James Cook was sent from England on an expedition to the Pacific Ocean to observe the transit of Venus from Tahiti, sailing westwards in HMS Endeavour via Cape Horn and arriving there in 1769. On the return voyage he continued his explorations of the South Pacific, in search of the postulated continent of Terra Australis.

He first reached New Zealand, and then sailed further westwards to sight the south-eastern corner of the Australian continent on 20 April 1770. In doing so, he was to be the first documented European expedition to reach the eastern coastline. He continued sailing northwards along the east coast, charting and naming many features along the way.

He identified Botany Bay as a good harbour and one potentially suitable for a settlement, and where he made his first landfall on 29 April. Continuing up the coastline, the Endeavour was to later run aground on shoals of the Great Barrier Reef (near the present-day site of Cooktown), where she had to be laid up for repairs.

The voyage then recommenced, eventually reaching the Torres Strait and thence on to Batavia in the Dutch East Indies (now Jakarta, Indonesia). The expedition returned to England via the Indian Ocean and Cape of Good Hope.[16]

Cook’s expedition carried botanist Joseph Banks, for whom a great many Australian geographical features and at least one native plant are named. The reports of Cook and Banks in conjunction with the loss of England’s penal colonies in America after they gained independence and growing concern over French activity in the Pacific, encouraged the later foundation of a colony at Port Jackson in 1788.[17]

New South Wales

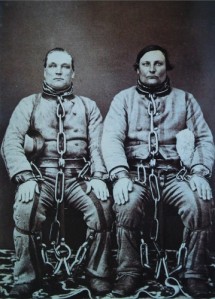

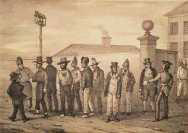

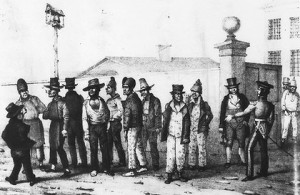

On 18 August 1786 the decision was made to send a colonisation party of convicts, military, and civilian personnel to Botany Bay. There were 775 convicts on board six transport ships. They were accompanied by officials, members of the crew, marines, the families thereof and their own children who together totaled 645. In all, eleven ships were sent in what became known as the First Fleet. Other than the convict transports, there were two naval escorts and three storeships. The fleet assembled in Portsmouth and set sail on 13 May 1787.

The fleet arrived at Botany Bay on 20 January 1788. It soon became clear that it would not be suitable for the establishment of a colony, and the group relocated to Port Jackson. There they established the first permanent European colony on the Australian continent, New South Wales, on 26 January. The area has since developed into Sydney. This date is still celebrated as Australia Day.

There was initially a high mortality rate amongst the members of the first fleet due mainly to shortages of food. The ships carried only enough food to provide for the settlers until they could establish agriculture in the region. Unfortunately, there were insufficient skilled farmers and domesticated livestock to do this, and the colony waited on the arrival of the Second Fleet. The second fleet was an unprecedented disaster that provided little in the way of help and upon its delivery in June 1790 of still more sick and dying convicts, which actually worsened the situation in Port Jackson.

Other Resources:

http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/convicts-and-the-british-colonies

http://www.awm.gov.au/atwar/colonial.asp

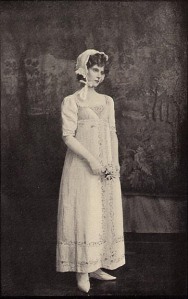

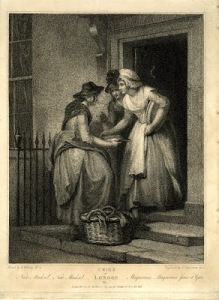

http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/convict-women-in-port-jackson